Charging Don Lemon with Violating the FACE Act Carries Significant Legal Risks

Career prosecutors understood the FACE Act’s limits, its risks, and its constitutional fault lines. None joined this case. The decision to invoke it highlights the motives behind the prosecution.

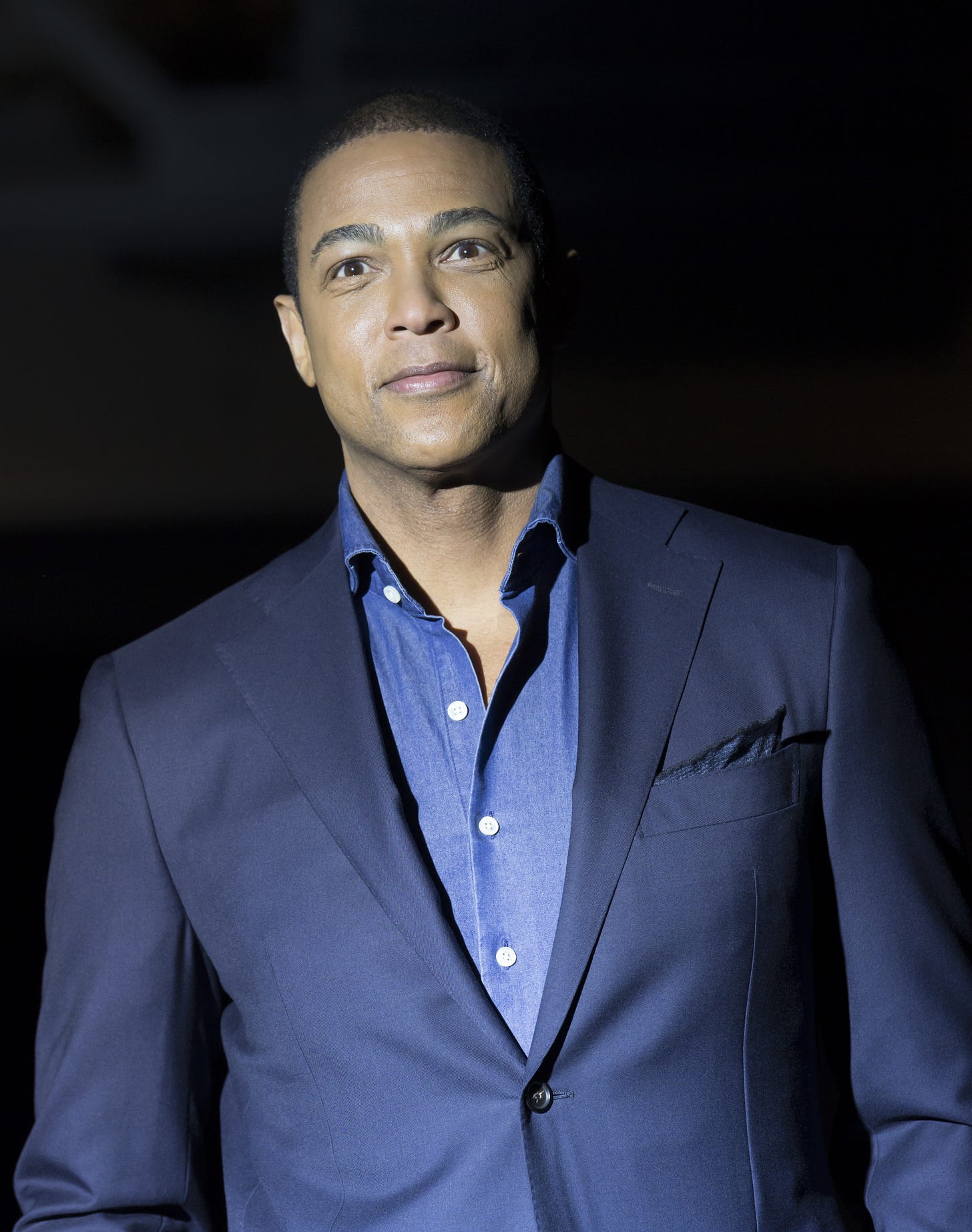

Last week, former CNN anchor Don Lemon and several others were arrested by federal agents in connection with a January 18, 2026, incident that disrupted services at Cities Church in St. Paul, Minnesota. The arrests instantly became national news.

The Department of Justice charged Lemon and his co-defendants — much to the surprise of many — with violating the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act, or FACE Act, a statute that until now has been used exclusively to prosecute interference with access to reproductive health services. Before this case, I am not aware of any instance in which federal prosecutors invoked the FACE Act to address misconduct at a house of worship.

But we shouldn’t be surprised. This novel and aggressive tactic has been percolating at the Justice Department for nearly a year, and the FACE Act has been a conservative lightning rod since it was signed into law by President Clinton in 1994.

When Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) introduced the bill, its focus was straightforward: addressing the escalating violence at reproductive health clinics. During the legislative process, however, Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) proposed an amendment extending the statute to places of religious worship. As part of a compromise, Senator Kennedy accepted the amendment, and the FACE Act passed in its current form.

For decades, career prosecutors at the Department of Justice intentionally left the religious-worship provision on the shelf, fully aware of its glaring constitutional and legal risks.

Its revival today is impossible to ignore.

The throughline is not subtle. The current administration has fixated on a narrative about FACE Act prosecutions, untethered from its actual enforcement history. Within a week of taking office, President Trump pardoned 23 individuals he claimed were improperly prosecuted under the FACE Act, and the next day the Department of Justice ordered prosecutors to cease enforcement of the Act absent exceptional circumstances.

A week later, Attorney General Bondi announced the formation of the “Weaponization Working Group,” which was charged, among other things, with examining “criminal prosecutions under the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act for non-violent protest activity.”

Then, President Trump issued Executive Order 14202, titled “Eradicating Anti-Christian Bias.” In it, he claimed that the “previous Administration engaged in an egregious pattern of targeting peaceful Christians, while ignoring violent, anti-Christian offenses.”

His proof? The “nearly two-dozen peaceful pro-life Christians” who were prosecuted “for praying and demonstrating outside abortion facilities.” At the same time, he claimed, the Department of Justice ignored attacks against “Catholic churches, charities, and pro-life centers,” creating an “atmosphere of anti-Christian government, hostility, and vandalism against Christian churches,” that he vowed to correct.

If one were unconcerned with facts, this narrative might sound persuasive.

But I am concerned with facts. And I spent years prosecuting FACE Act cases.

I prosecuted cases against decidedly non-peaceful anti-abortion extremists who blockaded clinics and intimidated patients. I also prosecuted pro-choice activists who spray-painted threats on religiously affiliated crisis pregnancy centers in the wake of Roe’s reversal. I was steeped in the FACE Act — its text, its history, its constitutional underpinnings. Before this administration, career prosecutors in the Civil Rights Division enforced the FACE Act without fear or favor, fulfilling its core promise: ensuring safe access to reproductive health services.

From that experience — and from defending FACE Act indictments against every conceivable legal challenge — I can tell you why the religious-worship provision of the Act has gathered dust. The reasons are not ideological. They are legal.

First, career prosecutors have long harbored serious constitutional concerns about 18 U.S.C. § 248(a)(2). Second, there already exists a well-established, constitutionally sound statute that addresses the same conduct: the Church Arson Prevention Act.

Here’s why that matters.

Section 248(a)(2) of the FACE Act purports to protect “the First Amendment right of religious freedom at a place of religious worship.” The problem is, the First Amendment secures no such right. It protects against government interference with the free exercise of religion. It does not create a freestanding right to worship at a particular place, enforceable against private actors. That right simply does not exist in our constitutional framework, nor does two centuries of precedent suggest otherwise.

Congress cannot legislate to protect a constitutional right that does not exist.

Courts, of course, are reluctant to invalidate statutes wholesale if unconstitutional provisions can be severed. So the question becomes whether Section 248(a)(2) can be justified on some other constitutional basis. The reproductive-health provisions of the FACE Act rest comfortably on Congress’s Commerce Clause authority: appellate courts have routinely held that reproductive health services are commercial in nature, and clinic violence and obstruction substantially affect interstate commerce.

Religious worship is different. There is no serious argument that worship is commercial activity, and I am aware of no authority suggesting otherwise.

That brings us to the Church Arson Prevention Act, 18 U.S.C. § 247. Section 247 makes it a federal crime to intentionally obstruct, by force or threat of force, a person’s free exercise of religious beliefs. In practical terms, it covers the same conduct the FACE Act purports to reach. But critically, it requires the government to prove that the offense “is in or affects interstate commerce” — a clear, court-tested constitutional hook.

That is why civil rights prosecutors have relied on Section 247 in cases ranging from Dylann Roof’s massacre at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, to a case involving an Arizona man who strapped a backpack to a toilet to intimidate worshippers at a California church. These were serious attacks on religious freedom, and prosecutors charged them under Section 247 — not the FACE Act.

Which brings us back to Minneapolis.

Why would today’s Civil Rights Division charge Lemon and others under the FACE Act instead of Section 247? Why choose the legally shakier statute when a constitutionally sound one is readily available?

I can’t (well, I can) speculate. But one fact is impossible to ignore: the conspicuous absence of career prosecutors from the indictment.

For decades, career prosecutors understood the FACE Act’s limits, its risks, and its constitutional fault lines. The decision to invoke it here says far more about the motives behind the prosecution than it does about the statute itself.

And it is the rule of law, not the talking points, that will have the final word.

Brilliant legal breakdown. The constitutional distinction between the Commerce Clause hook for clinics versus non-existent protection for religious worship is the kind of nuance that gets lost in political noise. The absence of career prosecutors from the indictment is telling. Saw similar patterns when politically motivated charges lack institutional buy-in and they tend to unravel on appeal.